This is What I’m Reading on Letter from Berlin, where I share thoughts on books that I’ve read and loved recently, along with other things I’m reading. The book links are affiliate. Thank you for your support.

I took the train to Poland this weekend. The train ran through thick cornfields and past thick forests; there were slowly moving white-and-red windmills in the distance and thick and fluffy clouds drifting across the clear blue sky. My destination was Wrocław, for my friend Laura’s son’s bar mitzvah. Laura chose Wrocław for the bar mitzvah because her grandfather grew up in Breslau; the synagogue we will be in this weekend was his childhood synagogue. Her grandfather was a lawyer in Berlin in the 1930’s and escaped shortly before Kristallnacht for the U.S.. You can read a little about Laura and her grandfather in this New Yorker piece from a few years ago.

It was my first time going to Poland (I don’t really count the brief traversing of the border at the Baltic that I did last year by bike). I feel sort of sheepish about it; I live in Berlin, after all, which is just 80 kilometers from the Polish border. When I was a child, Poland might as well have been Siberia. As a West Berliner, the farthest I ever went by car was to Brandenburg, to visit my friend Joanie’s father-in-law Hans. Each trip involved long waits at the border, I.D. checks by grumpy East German border police and car searches for contraband and, on the way back to West Berlin at night, people in hiding. My memories of those trips, now almost 40 years old, have taken on the hazy quality of dreams, but certain things are imprinted in my mind forever: the face of sheep peeking through a livestock truck in the dark as we waited for our car to be inspected at the border; sifting through the muddy sand at the village’s local lake to find small nuggets of amber in my palm; climbing into the neighbor’s tree to pluck sour cherries from its branches; looking for snails and slugs in Hans’s garden, a bramble of red currant bushes in the back; the cozy smell of his house, musty and damp.

As an adult in Berlin, there have always other places more pressing to visit than the neighboring country. And nourished on a steady diet of Holocaust literature throughout my life, I admit that Poland, in my mind, was mostly defined by the stories I had read about that terrible time. And so, on the train through the placid countryside, I couldn’t help but wonder if this is what people saw on their final train ride before annihilation. One family’s trip was particularly present in my mind.

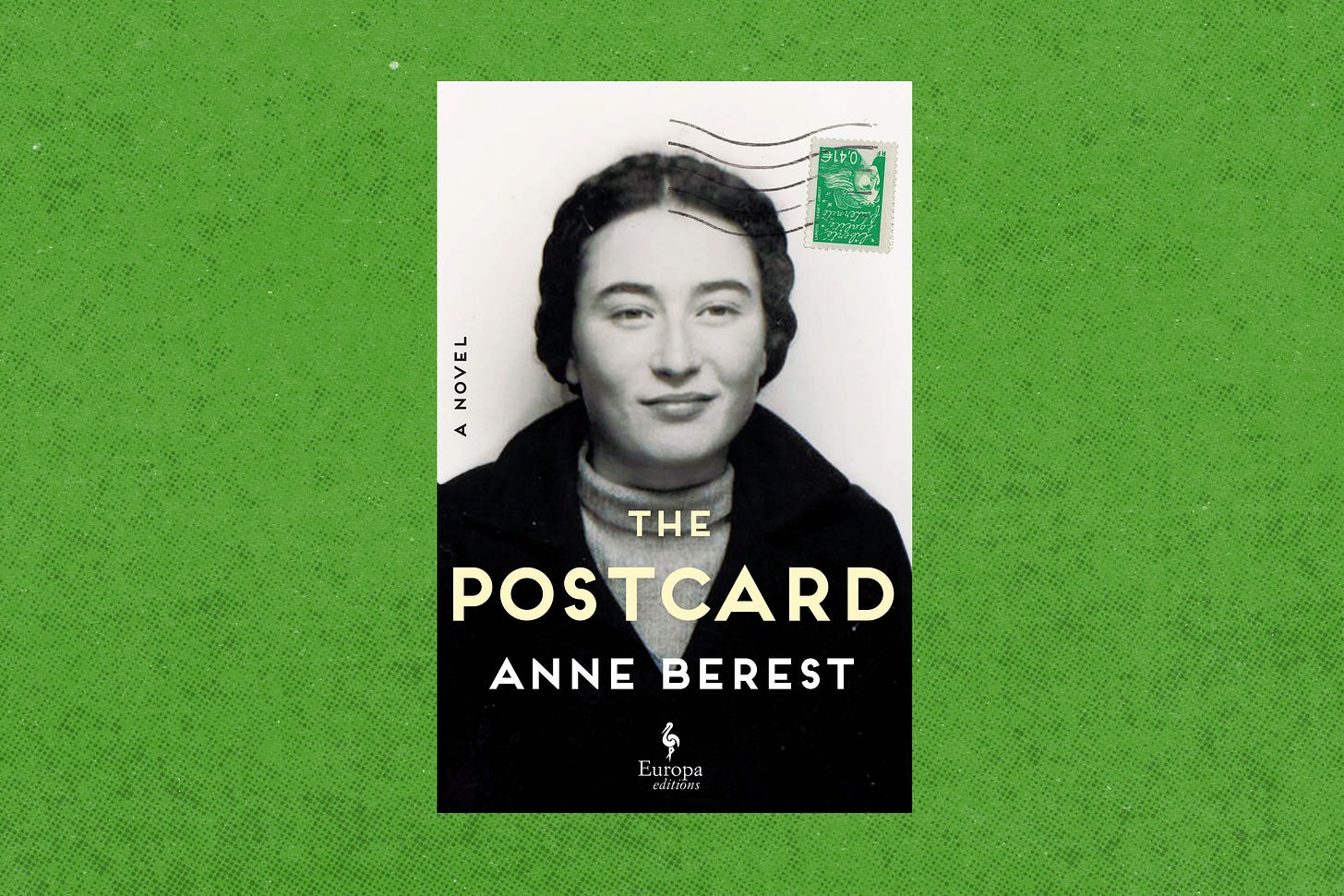

Last week in Italy, having finished all the books I took with me, I read Anne Berest’s The Postcard (on Libby), which tells the story of the Rabinovitch family. I don’t quite know why The Postcard ended up being the book I chose—it wasn’t on my more immediate list of books to read—but as I browsed my library’s offerings, I felt it reaching out for me.

The book, billed as autofiction, is a mesmerizing mixture of historical research and imagination. Anne is a young woman in 2003 when her mother Lélia receives a postcard with only four names on it: Ephraïm, Emma, Noémie and Jacques. These people—her mother’s maternal grandparents and aunt and uncle—were killed in Auschwitz in 1942. The only family member who survived was Myriam, Ephraïm and Emma’s oldest daughter and Lélia’s mother. But Myriam died a few years before the postcard was sent and neither Anne nor her mother Lélia has any idea who sent the postcard, which feels menacing. It gets put away and forgotten. Later, however, it spurs first Lélia and then Anne to delve into the essential mystery that is their family story.

Building on the research and writing that Lélia has done separately, Anne writes down the story of Ephraïm and Emma, who were married in Russia in 1919, then set off for Latvia, Palestine and eventually Paris, seeking safety and growing a family along the way, first Myriam, then Noémie and finally Jacques. Though they find a measure of stability in France, French citizenship eludes them—not that it would have saved them in the end—and when the Germans occupy Vichy France, the family’s fate is sealed. The only one to escape is Myriam, who survives the war in the south of France working for the Resistance.

Anne weaves their stories together with her mother’s and, of course, her own, dipping in and out of their conversations in a way that is reminiscent of Art Spiegelman’s conversations with Vladek in Maus—which I later learned was an inspiration to Anne during the imagining of the book. Anne has barely a connection to Judaism itself, but is haunted by the fate of her family, understanding eventually that her grandmother’s terrible loss has affected the family in a way that transcends generations.

The book, peppered with astonishing revelations, is masterfully constructed and written, the layers of history peeled back cunningly as it moves both forward and backward, from current-day Paris to revolutionary Russia, from the fastidious bureaucracy of Vichy France to the murderous mayhem of Auschwitz, from the crowded streets of Lodz to the wild isolation of Provence. Anne feels propelled in her work by an invisible hand, pushing her to uncover more, to learn more, to bear witness, to leave no stone unturned. She wonders if the invisible hand is Noémie herself, reaching out to her from the beyond. What results is a book that is impossible to put down, impossible not to be moved by, a text that is both highly personal and a general call against forgetting, now that the last generation of survivors is leaving this earth.

Another great book I read this summer was James by Percival Everett, which turns the story of Huckleberry Finn on its head and makes his companion Jim the center of the narrative. It is here that I must confess that I never read The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn—I started it as a child but could not fight my way through its cumbersome thicket of dialogue and offensive language. But I know the general outline of the story. Do you have to have read Huckleberry Finn to appreciate James? I don’t believe you do, though, of course, if you have read it, I assume that you will be privy to far more nuance and meaning in James than an ignorant reader like me.

Still, I appreciated so much the narrative that Everett crafts around James, a man of dignity and integrity who grapples with complex feelings towards Huck (I won’t give away the twist that Everett eventually reveals) and who must constantly weave in and out of a linguistic disguise that he and the other enslaved people develop to survive the savagery of slavery. It is funny and philosophical, brutal and thought-provoking. James has been long-listed for the Booker Prize and is being adapted for screen by Steven Spielberg.

Currently reading: Skippy Dies by Paul Murray

Next in my queue: The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki

Finally cracking to keep Hugo company: The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien

For those who have not read James or who also struggle to read dialog, I strongly recommend the audio book which is brilliantly done.

Guilty confession, after many years of following your blog and now here, I just read My Berlin Kitchen. Your writing, honesty, and perseverance are an inspiration- ‘leap and the net will appear’ was just the message I needed to hear, again.